When learning guitar, you will find that there’s a useful way to record music other than audio, and it’s by writing. There are three ways in which guitar music is written: music sheets, chord sheets, and tabs. You will find in this article the basics to make sense of what’s written in each so that you can practice and play your favorite songs!

Let’s get started with notes!

To read music, there are two elements to bear in mind: melody (what will be played) and rhythm (when and for how long will it be played). Notes, for that matter, are the unit for melody. Notes have two ways to be named. In both of these systems, the reference is the scale of C major:

- American Standard – A B C D E F G

- European Standard – A H C D E F G

Sometimes, there will be a symbol next to the note; it can be either:

- # – Sharp, which means the note must be played half a step higher.

- b – Flat, which means the note must be played half a step lower.

Tune yourself first so you can tune your guitar

As with learning any language, you have to know how things sound in that language to learn how to read it. The best ways to do this are either using a piano or keyboard to listen to the note you’re looking for, using a diapason (which are usually tuned to a perfect A), or going for a guitar tuner (there are apps for this as well). Take some time to get familiar with how each note sounds. Some people will have a better innate ability to identify notes, but this is a skill that can be worked. With time and practice, you can even get used to tuning your guitar by ear, because you will be familiar with the notes already. The standard tuning for a guitar, if you didn’t know already, from the 1st string (the highest in pitch) to the sixth, is e – B – G – D – A – E.

Okay but, what does this ‘step’ thing mean?

In music, notes go up or down in a default scale by a certain value. In the scale of C major, for example, there is a full step between C and D, as well as between D and E. However, you can take half a step up from C, and you will find C# (or Db, depending on the scale you’re using). There are exceptions to this rule. Between E and F, and between B and C, there is half a step, meaning there’s no new sharp or flat note in between. A B# would sound exactly like C.

On your guitar, this can be better seen on your fretboard: each fret moves half a step up from the original open note. For example, if you place a finger on top of the D string in the 3rd space, you will get an F, you’re going a step and a half, or three half-steps (D to E to F).

Got it. What are scales, though?

Different scales respond to different ‘step’ patterns. There are many, but let’s focus on the most important scales for a guitar player. For every example, C major will be our reference:

Diatonic-heptatonic Scale

Diatonic scales are the ‘normal’ scales, with 7 notes for every octave (an octave is an interval between a note and its equivalent with higher or lower pitch). These can be major (imagine major as happy) or minor (imagine minor as sad).

For example, the C major scale would be C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C. The pattern in steps for this one would be full-full-half-full-full-full-half.

The C minor scale would be C-D-Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C. The steps pattern here is full-half-full-full-half-full-full.

Pentatonic Scale

The pentatonic scale is a very fun scale, with 5 notes for every octave, that guitarists use for speed exercises on the fretboard and to improvise solos. It is also known as the Asian Scale for its wide use in Chinese music for thousands of years. The pentatonic scale for C is C-D-E-G-A-C. You can transpose and use the notes in this scale in every song to improvise your solos!

Chromatic Scale

This scale is all-inclusive; it takes into account every note (every half step) in an octave. Therefore, there are 12 notes for every octave: Starting from C, it would look something like C-C#-D-D#-E-F-F#-G-G#-A-A#-B-C.

How can I interpret chord sheets?

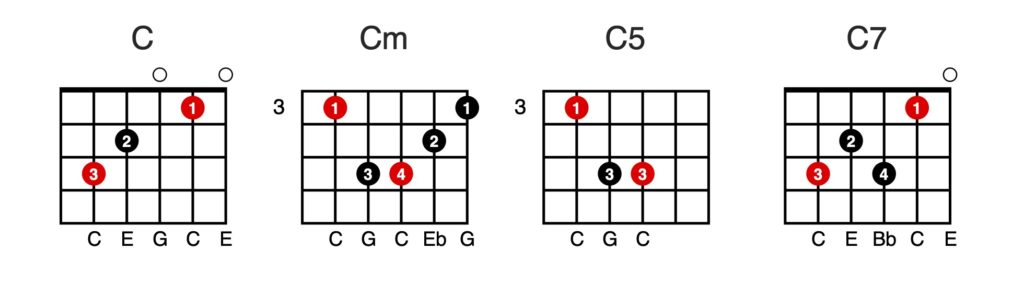

In a chord sheet, you will usually find the chords you ought to use on top of the lyrics for the song. Chord notation can be interpreted as follows:

Major chords are represented with its main note as-is. It is composed by the tonic (the root note) and the 3rd and 5th notes in its respective scale. For instance, the C chord would be C-E-G.

Minor chords are represented with its tonic with an m beside it. It is composed by the tonic and its 3rd and 5th notes in the minor scale. For instance, Cm would be C-Eb-G.

Power chords are represented by placing a 5 beside the tonic. This means only the tonic and its 5th note will be played. This is very convenient since power chords don’t have a distinction between major and minor. So, the power chord for C (C5) will be C-G.

Chords with added notes will have a number beside the tonic that matches the note that is being added, with an indication if that note is augmented (aug) or diminished (dim) by half a step. It is simpler than it sounds; trust me. For example, chords with an added seventh (7) are very common in rock and pop and are used to build tension, because they give the feeling of “being almost there”. An added seventh, in this case, is a full step below the upper octave of our tonic, as follows: C with an added seventh (C7) would be C-E-G-Bb.

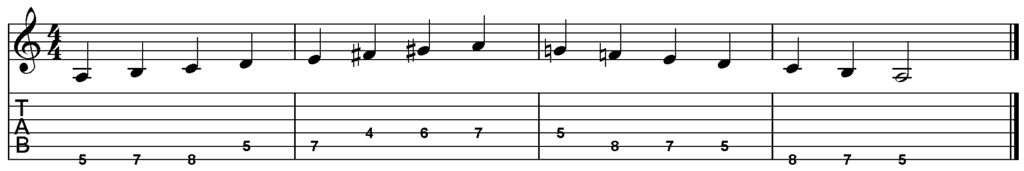

How can I interpret tabs?

Tabs are fairly easy to understand since the way they’re written is like looking at your guitar. What you see is what you get: the lines represent the six strings in a standard guitar, from top to bottom (E-A-D-G-B-e). The numbers in each line respond to the fret you should be pressing to obtain the note you need, in consecutive order. Piece of cake, right? But it feels like something is missing…

Why should I read sheet music if tabs are a thing?

Tabs are a good way to familiarize yourself with the fretboard, and they hold some value to copy riffs and solos. But there’s missing information, like a quicker, simpler understanding of the notes about to be performed and the exact rhythm in which they’re going to be played. Plus, silences aren’t notated in tab form. This is why tabs are usually paired with a standard music sheet, to include the information the tab is missing. Read more about how to read sheet music here.

Now that you know the basics, it’s time to practice! Start slow, just by interpreting the notes. Forget the rhythm at first. Then, if you’ve incorporated sheet music to read, get a metronome and start reading the rhythm. Then put your best efforts in doing both, slowly. Build up your speed until you’re happy with your reading skills.